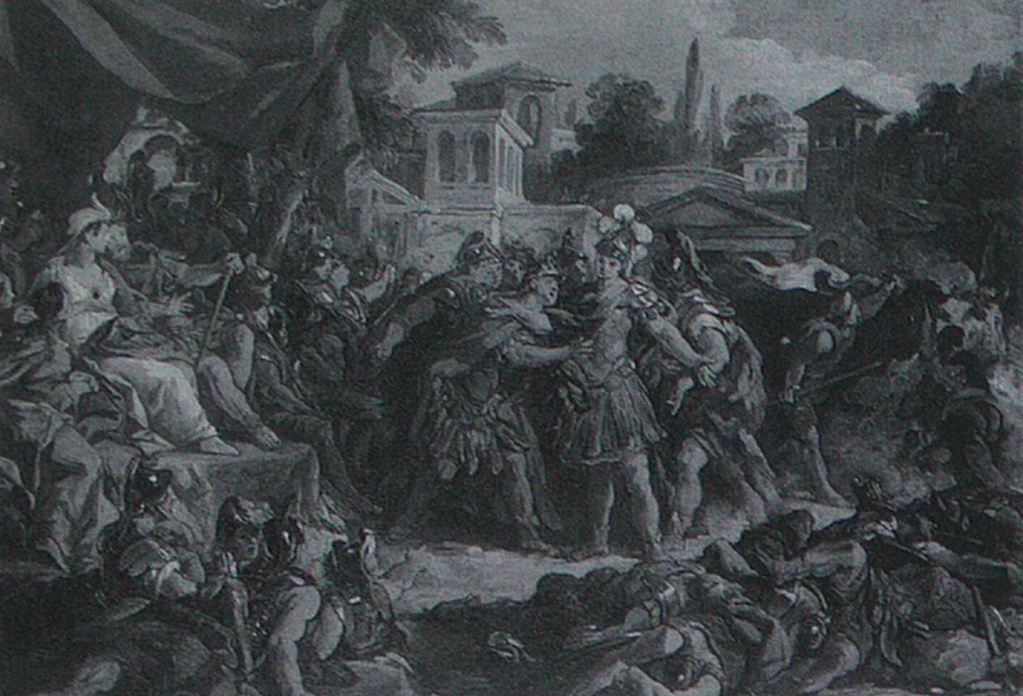

Rome, circa 1742, Oil on Canvas

The source of the subject for De Troy’s painting is Ovid, Metamorphoses (Briere G., Dimier L. 1930). Originally painted circa. 1742, it depicts Jason, in the centre, miraculously taming two fire-breathing bulls during his quest for the Golden Fleece. To the left of the painting he is watched by Aeetes, the King of Colchis, and by his daughter Medea. Jason holds protective magic herbs that was provided by Jason’s lover, Medea. This oil sketch was created in preparation for a much larger painting, which, in turn, acted as the model for a tapestry woven in the Gobelins workshop in Paris. Several similar sketches were also made, circa 1742, depicting Jason’s life; such as The Combat of the Soldiers Born From Serpent’s Teeth, and The Departure of Jason and Medea after the Conquest of the Golden Fleece, both shown below (Leribault 2002, p. 380).

Compositional Technique:

Several elements, inherent in the painting, informed the aesthetic and artistic intention of the composition; such as movement, density of sound, texture, space, and counterpoint between the organic (depicted by the crowd and the bulls) and the architectonic (depicted by the building structures in the background). The form of the work is suggested by the narrative aspects of the painting and initially focuses on sounds provided by the gathering and movement of the crowd. The listener’s perspective is shifted throughout the piece, and is placed in various locations within the painting.

The first phrase of the work is primarily concerned with the movement and somewhat chaotic utterances of the crowd. A steady rise in dynamics of sound and ‘swirling’ staccato-like effects, builds the ominous tension which crescendos with layered bull roars. The second phrase of the composition, sees the introduction of the bulls; the listener’s perspective is shifted to centre of the painting, with the raucous din of the crowd drowned out by the strength and fury of the two animals. My artistic intention for this section of the work is to convey a sense of unbridled fury, presence, and strength. As the bulls begin to be tamed, their roars are spectrally stretched or blurred; diffusing the tension after the initial sonic ‘shock’ and resolves to more serene timbral structures. Certain elements in the painting are employed to create a sense of motion within the piece, such as the ‘whipping’ motions of the bull’s tails. The final phrase of the work concerns the resolution of the tension, with the calming of the bulls, dispersal of the crowd, and expansion of the perception and perspective of the listener’s distance, with the dissolution of the the crowd and bull sounds.

The sense of space is also modulated in the three phrases of the work; beginning with the circular movement of the crowd — the space is all encompassing and sets the sonic landscape of the work; the second phrase the space is contracted, to focus on the bulls in the centre of the painting; finally, the space is expanded and becomes more diffuse to imbue the piece with a sense of serenity, or ‘moving away from the madness of the crowd’ and to contrast the hitherto anger, strength, and presence of the rampaging bulls to their taming.

Bibliography:

Briere G. & Dimier L. (1930) ‘Les Peintres Francais du XVIIIe Siecle’ vol. 2, no. 54. pp 26-27, 37.

Leribault, Christophe. (2002) Jean-François de Troy (1679-1752). Paris : Arthena.